|

Liu Fang's Passionate

Pipa - Traditional Chinese Music is in Her Heart and Soul

by Paula E. Kirman, June 24, 2001

For Liu Fang, traditional Chinese music is not only in her heart, it is in her soul. She was born in 1974

in the province of Yunnan and began learning the pipa, a Chinese lute, at the age of six. She began performing at age eleven,

including a solo performance for the Queen of England during the royalty's visit to China. After graduating from the Shanghai

Conservatory of Music in 1993, where she also studied the guzheng (a Chinese zither), she continued performing to critical

and audience acclaim. Moving to Canada in 1996 was a turning point in her career, as she began touring Canada and the United

States, playing various musical festivals in North American and Europe and making various television appearances. CBC Canada

and its French station Radio Canada recorded four of her concerts and she has received several awards from the Canada Council

for the Arts. Most recently, she was awarded the Future Generations Millennium Prize in June of 2001. One of only three winners, this prize is awarded to young performers seen to have extremely bright futures.

In the words of the jury: For Liu Fang, traditional Chinese music is not only in her heart, it is in her soul. She was born in 1974

in the province of Yunnan and began learning the pipa, a Chinese lute, at the age of six. She began performing at age eleven,

including a solo performance for the Queen of England during the royalty's visit to China. After graduating from the Shanghai

Conservatory of Music in 1993, where she also studied the guzheng (a Chinese zither), she continued performing to critical

and audience acclaim. Moving to Canada in 1996 was a turning point in her career, as she began touring Canada and the United

States, playing various musical festivals in North American and Europe and making various television appearances. CBC Canada

and its French station Radio Canada recorded four of her concerts and she has received several awards from the Canada Council

for the Arts. Most recently, she was awarded the Future Generations Millennium Prize in June of 2001. One of only three winners, this prize is awarded to young performers seen to have extremely bright futures.

In the words of the jury:

"Liu Fang's mastery of the pipa and the guzheng

has established her international reputation as a highly talented young interpreter of traditional Chinese music. She aspires

to combine her knowledge and practice of Eastern traditions with western classical music, contemporary music and improvisation,

thereby creating new musical forms, uniting different cultures and discovering new audiences." She is not only talented, but also very well spoken. I had the pleasure

of interviewing Liu Fang and having her talk about her musical career and how she became so proficient on two very difficult

instruments.

Paula: What is your musical training and background?

Liu Fang: My mother

is an actress of Dianju (similar to Peking opera). I had the chance to listen to music even before I was able to speak. My

mother always took me with her to rehearsals and sometimes also to the performances. I always sat there quietly during the

performances and never made trouble for my mother, because I was very much attracted to the music, the singing and dancing

on stage. When I was five years old, my mother began to teach me to play the Yueqin (a moon-shaped lute playing with a plectrum).

When I was six years old, she bought me a pipa, and I began to learn the instrument. My teacher was Prof. Zheng Qinrong from

the Yunnam Institute for the Arts. I love the instrument and made fast progress. I gave my first public performance when I

was nine years old, and began to receive several prizes for provincial and national competitions. Meanwhile, I got the chance

to perform with different performing troupes in many concerts, including a concert for the Queen of England. In 1990, when

I was 15 years old, I went to study at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, where I studied the pipa and guzheng, and got systematic

training in Chinese music in general and had intensive contact with Western classics. Upon graduation, I went back to my hometown

of Kunming, working as a pipa soloist at the Kunming Music and Dance Troupe. At the beginning of 1996 I moved to Canada with

my husband and have been living in Montreal.

I must say that I feel very happy to be in Canada. The audiences are great

and open- minded. Before I came to Canada, I never thought I could live on my music in the Western World until my first concert

in Montreal in 1996. I realized that my performance could touch the heart of so many people. This gave me immense courage

to continue my career as pipa soloist. Later on, my husband quit his job and became my manager. I began my international career.

Thanks to the support from the Canada Council for the Arts, my career has been developing very rapidly. By now I have given

four European tours and performed at many festivals across Canada and several concerts in the USA and Columbia. Radio-Canada

and the CBC have also given me great support. Six concerts were recorded in the last three years by Radio-Canada and Radio-

France recorded one. I had also the chance to perform on TV and for film music.

I am very happy to premiere the pieces

composed by Canadian composers such as Murray Schafer, Melissa Hui and Chantale Laplante. I had the chance to perform with

the Japanese Chamber music ensemble - Nishikawa Ensemble and premiered several pieces composed by David Loab (USA), Diago

Luzuriaga, Yoshiharu Takahashi (Japan). I have gotten the chance to perform with symphony orchestras and perform pipa concerti

composed by Tan Dun and Zhou Long. I also had opportunity to collaborate with master musicians from India, Japan, Vietnam

and the Arabic countries. This gives me great possibilities to explore the musical languages. Indeed, I had wonderful experiences

working with them.

I am now the featured artist of the Philmultic Management & Productions Inc. (Montreal, Quebec,

Canada).

Paula: What are the biggest challenges of playing the pipa and guzheng?

Liu

Fang: The biggest challenge is to fully express the soul of pipa and guzheng music in EVERY concert. To give a good concert

today doesn't mean that the concert tomorrow would also be as good. To have given 100 excellent concerts doesn't guarantee

that it would be always excellent in the future. This is a constant challenge more for the heart than for the skill. This

means that one needs always to learn to keep the heart in such a state as to give the music its life. For this, one needs

to learn many things besides music. I believe this is true for all kinds of music.

The pipa has existed in China for over

2000 years and its playing techniques are fully developed and are very complicated. To master these techniques is a challenge.

For instance, the tremolo with five fingers played from inside toward outside ("Lun" in Chinese) can be used as one of the

most important criteria to judge whether the player has mastered the instrument. The five fingers should give a clean sound

with equal strength. This needs a lot of practice and talent. If this technique is not good enough, the pipa sounds very uncomfortable.

In this case, there is no chance to interpret classical Chinese pipa music.

The repertoire for pipa is comparatively large

with some pieces handed down from the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD). There are several pipa schools in history with each having

their special ways of interpreting the classical pieces. The traditional scores combine symbols representing pitches and finger

techniques. There are many nuances in the music which cannot be put into the musical scores. Chinese classical music by nature

is very individual in character. The interpretation depends on the performer's understanding of the tradition and the personal

experience. There is no way to tell whose interpretation is the standard. Thus, the biggest challenge is how to respect the

tradition while keeping my own character. The judgment for good music should be left to the audience. Good music should touch

the heart and bring spiritual elevation.

The same is true with the guzheng. However, the guzheng is my second instrument.

In my solo recitals, one third of the program are guzheng solo pieces, intended to introduce classical guzheng music.

Paula: What or what are your musical influences?

Liu Fang: There are several

aspects in my musical influences:

The first influence is traditional singing. Partially because my mother is an opera

actrice, I had chance to list to traditional opera singing and a lot of folk songs in my childhood. This has been so deep

in my heart, so that when I am playing a tune, I am singing in my heart. When I playing a sad tune, I am crying in my heart.

I often heard from listeners that they heard singing in my music.

I love poetry and painting. This hobby helps me understand

Chinese tradition, which in turn helps me interpret classical Chinese music.

I also love Western classical music and the

traditional music from other cultural circles such as Indian, Japan, Persian, Vietnamese and Arabic music. I cannot say how

much these traditions influence my musical understanding, but surely they help me in communicating with the musicians and

audiences alike from other cultural backgrounds.

Paula: What do you like best about performing live?

Liu Fang: I enjoy playing.

Even when I practice, I wish somebody would be there listening. I enjoy performing in public, as I like the atmosphere in

a concert hall with many people where I can feel the spiritual and emotional vibration of the atmosphere. I would say, I enjoy

everything about performing live. I always feel happy when I have a concert. I feel a little depressed or lonely when there

is no concert for a long time. I also enjoy the time immediately after the concert to share the feelings and ideas with friends

and music lovers, listening their impression and understanding about the music. I often learn much from them. In particular,

I am very moved when somebody comes to me with tears in their eyes, telling me how much they enjoyed my music. This happens

quite often after the concerts. I feel that my music is loved and appreciated by many people, which is great motivation for

me to continue my career. Like many other musicians, quite often I also have to face financial difficulties, because a lot

of our income is used for travelling. But I don't care. I love my career. I also enjoy travelling: such as sitting in a plane

dreaming, or staying in a hotel. Comparatively, I don't like talking with people as much, because it is too easy to have misunderstandings

because of language. By making music, I feel the freedom and joy that I can never have by talking.

Paula: What are some definining characteristics of Chinese classical music that you convey in your

music? Paula: What are some definining characteristics of Chinese classical music that you convey in your

music?

Liu Fang: First, Chinese music is somehow related to the Chinese language. Unlike the western languages,

Chinese language has tonality: the same pronunciation with different tones represents different meaning, depending on whether

it is a flat tone, or sliding from a lower to higher pitch or from the higher to the lower, or a combination. The same thing

for music, except that there are more possibilities in tonality which is more sensitive and subtle. Thus, it is very important

to master the technique for both left and right hands: the right hand produces the sound by plucking the strings while the

left hand gets the right tonality by acting on the string, such pressing, pushing or several other actions that are difficult

to translate into English. Without having properly mastered these skills, it is impossible to interpret classical Chinese

pipa music. Just as Prof. Tran Van Khe put it: "The right hand gives the sound, but the left hand gives the soul to the music".

Therefore, one phrase in Chinese classical music is not simply a string of notes, but each note has its own life and meaning,

depending on how you play it in the context.

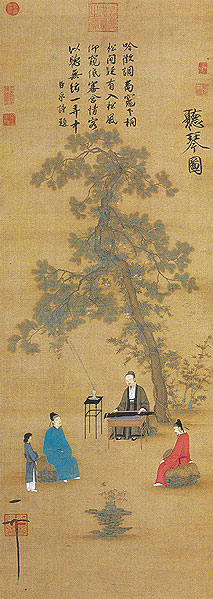

Secondly, Classical Chinese music refers to the art music closely related

with Chinese poetry. Therefore, it is not surprising that most of the classical pieces have very poetic and sometimes philosophical

titles. Traditional classical music in this sense is intimately linked to poetry and to various forms of lyric drama and is

more or less poetry without words. In the same manner as poetry, music sets out to express human feelings, soothe suffering

and bring spiritual elevation. Therefore, it is very important to understand the meaning and set the mind and the heart in

the right mood that is in "in tune" with the music, particularly when playing the repertoire of the "literary style" or civil

style, which are mostly slow and meditating. It can be very dull when just giving the sound without a meaning.

Thirdly, Classical Chinese music and traditional Chinese

painting are twin sisters. Take, for instance, the traditional painting for landscapes: there is no obvious focus in the picture,

but each part seems to have its own focus in such a manner that the variety of local character is in harmony with the whole

picture, including the empty parts. In traditional Chinese painting, the empty parts are very important too in order to give

the whole painting life. If everywhere were painted, there would be less freedom of imagination for the viewers in appreciating

the painting. In another words, the appreciating of painting is an interactive and dynamic process between the viewers and

painting. The same is true with classical Chinese music. Each phrase is one sentence followed by a certain silence in such

a way that the variety of pipa sounds and the silences (and sometimes noise) are combined harmoniously in forming the sound

poetry, creating a kind of dynamic link between the performer and the audience. A good performer can create such a link so

that the listeners can experience the power and the beauty of the music in a way like enjoying a beautiful poem and painting.

To achieve this, only the perfection of playing technique is not enough. One has to undertand the

spirit of the music, and pass that spirit to the listeners. The best result can be achieved with the purest heart one can

keep. That is, one must free the mind, and be humble such that the performer becomes the instrument. This is the goal that

I always pursuit, because I often have this experience of "up" and "down". In a live concert, if most of the time I am in

such a state, I am very happy. This happens often when the concert hall has very good accoustic and the audience are very

special (i.e. attentive and sensitve to the sound). There were times that I play almost the whole concert in such a state.

I felt very happy, and very satified after the concert. There were other times that it was difficult to control, and I was

often aware about the music notes in order to diliver it correctly. In this case, I felt very tired after concert, and not

so happy, even when I didn't make mistakes. I can also feel the audience's reaction, and I know exactly how much I have passed

the spirit of the music to the audience, even without listening how long they would applaude. It is a dynamical and heart-to-heart

process. Thirdly, Classical Chinese music and traditional Chinese

painting are twin sisters. Take, for instance, the traditional painting for landscapes: there is no obvious focus in the picture,

but each part seems to have its own focus in such a manner that the variety of local character is in harmony with the whole

picture, including the empty parts. In traditional Chinese painting, the empty parts are very important too in order to give

the whole painting life. If everywhere were painted, there would be less freedom of imagination for the viewers in appreciating

the painting. In another words, the appreciating of painting is an interactive and dynamic process between the viewers and

painting. The same is true with classical Chinese music. Each phrase is one sentence followed by a certain silence in such

a way that the variety of pipa sounds and the silences (and sometimes noise) are combined harmoniously in forming the sound

poetry, creating a kind of dynamic link between the performer and the audience. A good performer can create such a link so

that the listeners can experience the power and the beauty of the music in a way like enjoying a beautiful poem and painting.

To achieve this, only the perfection of playing technique is not enough. One has to undertand the

spirit of the music, and pass that spirit to the listeners. The best result can be achieved with the purest heart one can

keep. That is, one must free the mind, and be humble such that the performer becomes the instrument. This is the goal that

I always pursuit, because I often have this experience of "up" and "down". In a live concert, if most of the time I am in

such a state, I am very happy. This happens often when the concert hall has very good accoustic and the audience are very

special (i.e. attentive and sensitve to the sound). There were times that I play almost the whole concert in such a state.

I felt very happy, and very satified after the concert. There were other times that it was difficult to control, and I was

often aware about the music notes in order to diliver it correctly. In this case, I felt very tired after concert, and not

so happy, even when I didn't make mistakes. I can also feel the audience's reaction, and I know exactly how much I have passed

the spirit of the music to the audience, even without listening how long they would applaude. It is a dynamical and heart-to-heart

process.

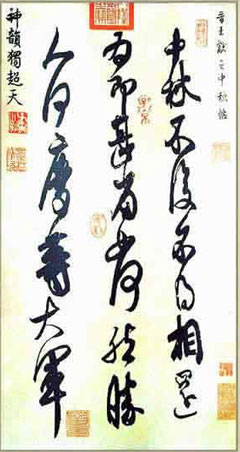

I want to add a few more words Regarding live performance

of Chinese classical music, I would say that the closest relative is Chinese calligraphy. I have always been interested in

calligraphy, and indeed, appreciation of great calligraphy gives me immense inspiration to my music playing. I don't practice

calligraphy myself, but I love this traditional art. And I understand the basic idea of calligraphy and its esthetic principles.

Chinese calligraphy has been regarded as the highest art among all arts in China. Through the study of master calligraphies,

I understand that the spirit in writing calligraphy is very much comparable to playing music. The energy, the feeling, and

the breath that gives life to the calligraphy are in a sense the same as playing classical Chinese music, although they belong

to totally different arts. The dynamics and movement of strokes of the brush, the line and the points, and the whole structure,

they are all comparable to playing the music. This is one of the major sources of inspiration for my music playing. I want to add a few more words Regarding live performance

of Chinese classical music, I would say that the closest relative is Chinese calligraphy. I have always been interested in

calligraphy, and indeed, appreciation of great calligraphy gives me immense inspiration to my music playing. I don't practice

calligraphy myself, but I love this traditional art. And I understand the basic idea of calligraphy and its esthetic principles.

Chinese calligraphy has been regarded as the highest art among all arts in China. Through the study of master calligraphies,

I understand that the spirit in writing calligraphy is very much comparable to playing music. The energy, the feeling, and

the breath that gives life to the calligraphy are in a sense the same as playing classical Chinese music, although they belong

to totally different arts. The dynamics and movement of strokes of the brush, the line and the points, and the whole structure,

they are all comparable to playing the music. This is one of the major sources of inspiration for my music playing.

Paula: What are your goals as an artist?

Liu Fang: I don't have a particular

goal. But I do hope to be able to collaborate with many composers, to let them understand deeply the character of the instruments

so as to compose great works for the pipa and maybe with other instruments. I also wish to compose my own music. My background

is traditional Chinese music. Since I moved to Canada, I have had good opportunities to contact with other traditions in the

World and play with master musicians such as Debashish Battarcharya (Indian slide guitar), Yegor Dyachkov (cello), Yoshio

Kurahashi (Japanese shakuhachi), Kohei Nishikawa (Japanese flute), and Tran Van Khe (Vietnamese zither). Recently I have produced

a CD featuring cross-overs of Arabic and Chinese traditional music with Farhan Sabbagh (Arabic ud and percussion) under the

Canadian label of Philmultic Management and Productions Inc.. I wish to continue with the collaboration with master musicians

from other traditions and gradually to be able to compose my own music by integrating the elements from different cultures.

I also wish to introduce classical Chinese pipa and guzheng music to every corner of the World.  |