I. Beauty, Horror + Biotechnology

Skin is the body part most easily altered by human

beings, ranging from circumcision to cosmetics to hair removal. Popular demand for aesthetic surgery and dermatology has soared

over the past decade. At the same time, tissue engineers have been learning to manufacture living skin in laboratories. Science

fiction explores the extreme possibilities of human-technology hybrids in the figure of the cyborg, a living creature with

electromechanical body parts.

Designers have confronted the biomechanical transformation

of the human body with horror as well as fascination. The beauty of bodies and objects is submerged in the realm of the artificial,

from synthetic materials to digitally manipulated surfaces. Industrial skins have assumed a life of their own. It is a life

whose pedigree, however, is more alien than human.

Video “Beauty, Horror and Biotechnology”

by Elke Gasselseder is a montage of clips from films about cyborgs, aliens, and artificial life. Each film comments on the

disturbing overlap between natural and artificial skins.

“Fibre Reactive” is an article of living

clothing. As Donna Franklin’s work makes clothing a host, a new symbiotic relationship between fungi and the wearer

is created. Although we are accustomed to wearing products made from living organisms, rare indeed is it that we wear materials

in a living state. “Fibre Reactive” allows the production of garments begin to link with nature’s rhythms

and the growth of organisms. Research into microorganisms gives the garment industry greater room for maneuvering, while putting

the conception of apparel into the context of imagination of the human skin, rather than as an independent material.

Photographer Peter Menzel has been documenting

the robot-making technology around the world. Second-Generation Face Robot was taken in Science University of Tokyo in 2000.

The laboratory’s focus is on developing robots into a type of socialized animal, or concentrating on the social interaction

between robots and humans. For robots to live together with people, the scientists must first make them feel friendly. Consequently,

the laboratory is particularly interested in robotics concerned with facial expressions as well as creating electronic structures

that emulate happy expressions.

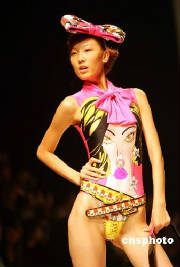

II. Erotics of the Artificial

Skin is the part of the other people that we touch,

and the part of us that we allow to be touched. Revealing one’s skin can be an expression of personal affection or public

exhibitionism. Skin-to-skin contact is central to human intimacy.

In an era when sexuality is the subject of scientific

study and medical control, objects with soft, washable surfaces and flexible latex skins reflect on our desires for hyper-cleanliness

and mediated—rather than direct—touch. Contemporary eroticism often comes clothed in latex. An aesthetic of hygiene—kinky

and clean—envelops the surfaces we touch.

In their work “TechnoLust,” industrial

designers Carla Ross Allen and Peter Allen adopt a hard avant-garde science fiction approach, using playful imaginings that

originate in cartoons and online games, including 3D scanners, vacuum plastics, nano chips and LED screens as part of high

tech fashion equipment, which when worn transport individuals to a virtual erotic game playing world. Another artist Matthieu

Manche produces a work from latex materials with its implications of sexual passion and clinical diagnostic function. Functionally

latex clothing can not only be worn again and again by many different people it also alludes to the extendability of the skin

and body.

Argentine artist Nicola Costantino creates objects

that comment on the meat and leather industries. In the surrealist tradition, her handbags and shoes of “Human Furrier”

series are imprinted with tiny images of human nipples and anuses. Recalling the look of ostrich leather, the effect

is at once decorative and alarming.

III. Body Armors

Skin has a vital interior beneath its dead outer

surface. Skin’s middle layer, the dermis, is made of collagen and elastic fibers, while the innermost layer of fat insulates

heat and protects against injury. These hidden layers provide the supportive padding that shapes the body’s outer envelope.

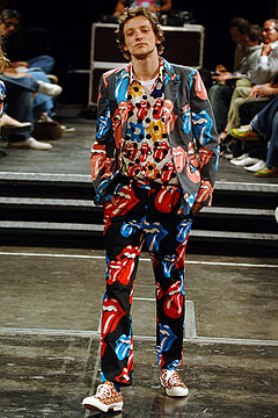

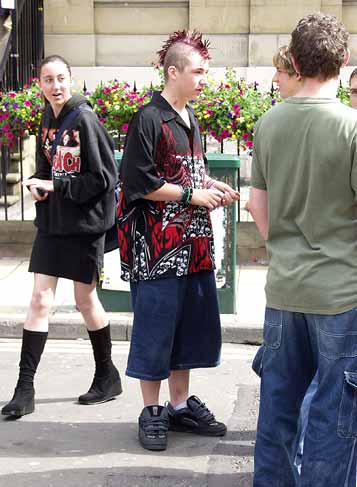

Clothing supplements the skin’s defenses

against the elements. Contemporary designers have hyper-extended fashion’s protective capacity, creating garments that

serve as portable environments in a world defined by leisure and spectacle as well as by nature, terror, and war.

Italian artist Alba D’Urbano took pictures

of her own naked body, copied them onto flat cloth, and then tailored it into a three-dimensional suit that can be worn. These

designs reveal that which was originally hidden by clever ‘packaging.’ Through the meticulous manufacturing process,

society’s views and thoughts on the female body are revealed. D’Urbano’s recreations force these imaginings

on the female form to the surface, conveying sarcasm towards their creation through cultural property.

Grado Zero Espace Ltd. of Italy combines science

labs, research on fiber materials, and designs from a variety of industries in their efforts to research and create highly

functional items. This jacket, titled Cooling System, is based on designs for the US army during the Cold War. Within this

combat clothing is a cooling system used by astronauts. Using fifty meters of 2mm-wide plastic tubing, this design allows

soldiers to fight in very hot conditions, and allows humans to quickly adapt to changing environments despite our biological

limitations.

From being a part of the body to becoming a part of

our living environment, clothing can now truly interact within the space between our bodies and our environments. The Transformables

by Italian designer Moreno Ferrari, was an epochal transformation of our contemporary environment and culture into clothing,

which represented the simultaneous evolution of the human body into organisms that carry their homes with them as they move

among different environments.

IV. Luminous Objects, Luminous Surfaces

Skin is said to “glow” in response

to youth, health, or happiness. A luminous object appears curiously alive. Artificial light signals the presence of electricity,

the life force of digital and mechanical systems.

While some lighting systems serve to illuminate an object, environment, or task area,

others emit low levels of light to foreground the fixture itself. Light emanates from pendulous bladders or from bulbs festooned

with silicone growths. Luminous rubber skins peel back to direct the flow of light. Such objects invite physical contact as

their dull interior illumination draws attention to the surface, infusing their skins with an alien energy, at once comforting

and strange.

The ‘luminous objects’ featured in

Second Skin are characterized by the delicate relationships between ‘lighting’ and ‘life’.

One example is JINZI lamp designed by Swiss architecture duo Herzog and de Meron for Belux AG. JINGZI resembles a giant, tail-wiggling,

forward-moving spermatozoon. Its exterior is made of silicon; with the electronic components wrapped inside of this translucent,

membrane-like silicon skin. Interestingly, this lamp-set can be used for multiple purposes; it can serve as a chandelier in

the restaurant, as well as a ground lamp prostrating limply on the floor. Given a lampstand, it can also be erected and turned

into a standing lamp. To turn on the light with a seamless exterior, all we need to do is to pinch the rear silicon tube and

hold it for three seconds.

Blanket designed by Ditte Hammerstroem has turned

an ordinary object of domestic comfort into a responsive organism in her work. The edge of the blanket is bordered with tiny

light bulbs, providing illumination for reading in bed or in an armchair. The border lights up when touched. The wool outer

layer can be removed and washed.

Superpatata—a multi-colored latex capsule

filled with salt— is a highly experimental piece of lighting design by Héctor Serrano in cooperation with a Dutch company,

droog design, in 2000. Various skin qualities and experiences—thick and thin, loose and tight, pinching and tearing—are

all projected onto this piece of work. We may determine the brightness, and shift between direct and indirect modes of lighting,

by simply altering the shape of the latex capsule. The latex capsule can also serve as a pillow or a buffer. In addition,

when piled up, these Superpatatas would immediately turn into a shining piece of art collection in the house.

V. Living Architechture

Skin is a surface that flows from the outside of

the body into its internal cavities. New building materials combine surface and structure, creating fluid exoskeletons. Materials

such as glass and plastic become plump and pendulous, while the walls of buildings bend, morph, and glow. Flat materials are

folded or warped to create load-bearing structures as well as walls with diverse functions. Skins weave through space, shifting

from inside to outside, top to bottom, ceiling to floor.

The challenges faced by contemporary architects

have become completely different from those faced by masters like Michelangelo, Mies van der Rohe, and Louis I. Kahn. The

idea of pursuing eternal, unchangingly beautiful architecture has been challenged. How can architects design something that

can capture and respond to the demands of daily life? Only by simultaneously fulfilling disparate demands such as, for example,

environmental protection, media accessibility, adjustability to fashion, and internal function can they meet the challenges

of our era.

Jan and Tim Edler, the young duo of architects

from Germany have been extremely successful in the current trend of fusing visual media with architectural surfaces, and their

future continued success is expected. Converting the traditional surfaces of architecture into facades with continuously changing,

computer-controlled video causes buildings to switch from their fixed, passive roles to active, speaking ones. On the front

façade of Kunsthaus Graz (art museum), Austrian, designed by Peter Cook, one of Archigram’s leading figures, Jan and

Tim Edler added 930 round fluorescent lamps, and by slightly modulating each lamp’s intensity, a surface that forms

an uninterrupted visual dialogue with the public is created.

KOL/MAC, a two-man team of architects from New

York, developed a new building material, called INVERSAbrane, in an R&D project completed in cooperation with DuPont.

The idea for it derived from the structure of soap bubbles. Besides serving the basic function of forming a hard, fire-resistant

façade that can freely adjust to environmental conditions, it is intended to provide the building appropriate security and

protection and replace the existing membrane structures in green architecture.

The holes in the wall may be used to collect

and store water that may also be used with the sprinkler system. The wall may also be penetrated with other channels and at

specially controlled intervals may collect solar energy. They can filter air as it passes from the outside and collect pollutants

that are then automatically washed away with natural rainwater. INVERSAbrane’s appearance is a reflection of the coming

trend of fusing architecture with biochemical systems; it converts the simple exterior walls of the past to new multifunctional

skin layers.